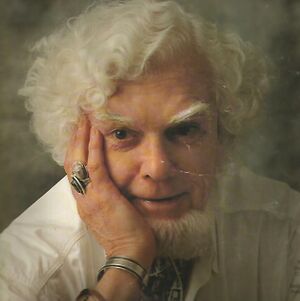

Thomas Anthony Kerrigan

The topic of this article may not meet Wikitia's general notability guideline. |

Thomas Anthony Kerrigan (b. March 14, 1918, Winchester, MA., USA – d. March 7, 1991, Bloomington, IN., USA ) was an Irish-American man of letters, poet, essayist, art critic and award-winning translator, best known for his seven-volume translation of the works of Spain’s great heterodox and passionate existentialist Miguel de Unamuno₁, and the first and last to render Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges into English₂.

Early Life

Kerrigan was conceived in the Panama Canal Zone, the world’s most dramatic and effective frontier, “lying as it does between two mighty oceans and two mighty continents” ₃. This undoubtedly determined his destiny for he would live at saltwater’s edge for most of his life, first in Cuba and New England as a teenager; Florida and California as a young adult, and back and forth between the islands of Mallorca and Ireland for the greater part. Late in life he returned to a self-imposed exile in the USA.

Although he led a privileged existence in Cuba, it came to an abrupt end at the age of twelve with the early death of his father—the Havana assistant to manager of United Fruit Company—at forty. His world came asunder, and this marked the beginning of what would be a deracinated life. Although he considered himself an autodidact, Kerrigan was to attend a spate of schools—eight in four years—both in Cuba (Christian Brothers in Havana) and on the East and West Coasts of the USA. He is said to have achieved a certain maturity at the age of 15, after seeking out the Boston Symphony Orchestra, reading the Karamazov Brothers and graduating from Winchester High School₄. He then went on to study at the University of San Diego (formerly San Diego State College).

Career

It was at this period that Kerrigan began a literary career and live by his pen, as well as to marry his first wife, at seventeen, Marjorie Burke, an ancient Greek scholar, who bore him his first son, Michael Kerrigan. Both being communists at the time, the Party sponsored their underage marriage, as well as to provide Kerrigan with a job, since the YCL (Young Communist League) was in control of the WPA Writers Project in San Diego. He wrote studies for the American government on architecture and agriculture₅. Meanwhile, his fealty towards communism was fast waning and he was subsequently expelled for sympathizing with a Trotskyite, which he’d soon become too. Some of his fellow travelers included Ward Moore, Harvey Breit, Kenneth Patchen or Carl Foreman₆, who all went on to greater things, as he himself did. By then he’d come to the attention of Hoover’s FBI, which concocted a file of preposterous activities, such as planning to take over the Douglas Aircraft Company, where he’d been employed for a year₇.

At the outbreak of World War II, Kerrigan enlisted and was assigned to Intelligence Service to decipher and translate Japanese, as he’d previously studied the language while a nightshift taxi driver, in time becoming an instructor in Sino-Japanese at the University of California at Berkley. After the war he took up residence in St. Augustine, Florida, where he ran a weekly newspaper. Through his association with the St. Augustine Historical Society, he began translating for a living, initially of early Spanish chronicles of exploration, as a faculty member of the University of Florida₈.

Spain, Ireland—and the USA

Mallorca, Spain

Like many an American before him, the pull of Europe (and adventure) was too strong to resist, and before the cutoff date for GI Bill benefits for study abroad, he eloped with Elaine Gurevitz, who had studied music under Carl Friedberg. She would become his second wife and mother of his five other children, all born in Europe. His first port of call was Paris, where he spent a year studying at the Sorbonne and where his daughter, the literary agent, Antonia Kerrigan, was born. He then moved to Mallorca to be close to the University of Salamanca—on the mainland—where all of Unamuno’s papers were kept. In 1961 he purchased what had been Gertrude Stein’s home during her Mallorca sojourn in the early part of the century, and from which she’d written a number of plays, claiming that “a certain kind of landscape induces plays” ₉. The same house from which Kerrigan, a little over a century and a half later would embark upon a fifteen-year project with Princeton University Press and the Bollingen Foundation to translate Unamuno’s most notable works. A thinker who was close to his heart and a project which he was encouraged to undertake by writers Edward Dahlberg and Sir Herbert Reed. And it was Robert Graves, whom Stein had encouraged to come to Mallorca, who had this to say: “It is very exciting to revisit Gertrude Stein’s distant corner of Palma which the Kerrigan’s have made their own […].”₁₀

Robert Graves landed in Mallorca in 1929 and was a magnet for a number of foreign intellectuals and artists who followed in his footsteps. There was also the Galician Nobel Prize winner, Camilo José Cela, who had moved to the island around the same time as Kerrigan did, who would further cement Mallorca as a literary center with his Papeles de Son Armadans, the literary journal he founded in 1956, as well as the Prix Formentor, an international literary award which he created along with poet and editor Carlos Barral. Kerrigan became a regular contributor to Papeles de Son Armadans₁₁ from its inception, and actively participated in many of Formentor’s yearly gatherings, as well as being Cela’s English translator.

Dublin, Ireland

In the late 1950’s, Kerrigan felt an urge to visit the country of his ancestors, and what was meant to be a mere fortnight, turned into a twenty-year-long affair with Ireland. The Kerrigans rented an apartment in Fitzwilliam Square, in the heart of Dublin, and decided to spend winters in Mallorca and summers in Dublin’s cooler clime. It wouldn’t be long before Kerrigan was moving in Dublin’s bohemian literary circles and contributing poetry and prose to the city’s main literary journals. Through the aegis of Dolmen Press, which published two books of poetry and one of translation and prose₁₂, Kerrigan was to meet and befriend the leading poets and writers of the day, among them: Austin Clark, Thomas Kinsella, John Montague, Liam Miller, Aidan Higgins, Desmond O’Grady, Sybil Le Brocquy and a host of others₁₃̷₁₄̷̷₁₅̷̷₁₆. He wrote about “The Troubles”₁₇, “The Travelling People” (Tinkers)₁₈, as well as introducing Spanish-speaking authors such as Borges, Unamuno, Pablo Neruda, and Cesar Vallejo to English-speaking audiences through his translations.

United States

Kerrigan’s relationship with North America was never severed. Not only did he work with Princeton and the Bollingen Foundation, but he made steady contributions to a number of magazines and journals throughout the years, including The Malahat Review, The Critic, Fiction, Exile, Confrontation, The National Review, The Texas Quarterly, Partisan Review, Atlantic Monthly, and Modern Age. He was a visiting professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1974, and lecturer at several universities, including the University of Chicago and the University of Michigan. From 1984 to 1991, he was a Senior Guest Scholar at the Hellen Kellogg Institute for International Studies, at the University of Notre Dame, Indiana, where he completed a new annotated translation of The Revolt of the Masses, by Spain’s preeminent political philosopher José Ortega y Gasset, which carried a forward by Kerrigan’s long-time friend Saul Bellow. He translated Atlas, the final book of Jorge Luis Borges, who considered Kerrigan the best of his English translators₁₉. While at the Kellogg Institute, Kerrigan, who was adamantly opposed to all forms of totalitarianism, and most critical of the Castro brother’s communist Cuba, not only translated exiled Cuban writers but visited the island for his last time in 1986, to report on what the newly literate were reading. The report appeared in no less than five publications₂₀. Up to the days before his death, Kerrigan was working on a comprehensive volume of poetry, yet to be published.

Works and Reception

Art & Criticism

In 1950, Kerrigan opened an art gallery (Kerrigan-Hendricks) ₂₁ on Oak St., around the corner from Lake Michigan in Chicago, whilst working as Fine Arts Editor for the American Peoples Encyclopedia₂₂. Leon Golub would the gallery’s most renowned artist₂₃, but Kerrigan, whose sights were set on Europe, would soon set sail for the old continent. However, his relationship with painters and sculptors would continue throughout his lifetime. He would meet and write about many artists: Miró, Picasso, Tapies, Millares, Solana, Saura, Vedova, and others. In Spain he became North American editor of Goya, that country’s leading art journal, as well as a regular contributor to Arts, in New York.

Poetry

Kerrigan’s poetry has been highly praised by a number of critics. The reception given to At The Front Door of The Atlantic was formidable: ₂₄

“[…] poems of extraordinary texture, bearing influences of Catholic Ireland… and bearing, also, great affinity with surrealist painters; strange and challenging appositions of situation, theme and emotion.

The word-manipulation is immense; the literary, artistic, religious, architectural and theological associations are innumerable; the humanity is undeniable. […]”

Hugh McKinley, “Immured in Simplicity”

The Athens Daily Post, September 7, 1969

“[…] I have described Mr. Kerrigan as a romantic poet. More accurately, his view of life is metaphysical… He appears to oppose the flux of life with the metaphysical permanence of the artist’s carefully wrought images. […]”

“[…] Mr. Kerrigan’s new collection of poems should establish him as one the most adept and authoritative poets of our time. I say “should” rather than “will,” for Kerrigan’s work makes few concessions to the general, is openly occasional, and uncompromisingly allusive.”

“The poems are lyrical without being rhetorical, easily constructed without being loose, intellectually alive without being cerebral, and always musical and precise in diction. […]”

Robin Skelton, The Malahat Review

(copyright © The Malahat Review, 1969)

October, 1969[1]

“[…] Kerrigan is not discovering a new thing; he’s working over the terrible complexity of having lived and having paid attention to it. And his questions, having the complications of much attention, have become ones which are often both hard and beautiful in their formulation.” (p. 5)

Colton Johnson, in Hierophant

(Copyright 1972 by Thomas Kerrigan), April 1972[2]

“Kerrigan’s poetry therefore relies on the perceptions of the mind that has studied the real places out there, the scenes we should enjoy if we came to stand where in memory he stands. Dublin, Chicago, Barcelona, Paris, the galleries of the early twentieth-century painters, whose forms he sometimes contemplates by translating their essential ideas of structure into attitudes about people or music or building—but always arriving at something that he can say vey succinctly.”

Jascha Kessler, in Parnassus

Fall/Winter, 1973, Pp. 223, 225-27[3]

Works of Poetry

- Lear in the Tropic of Paris, Tobella, 1952.

- Espousal in August, Dolmen Press [Dublin], 1968.

- At the Front Door of the Atlantic, frontispiece by Pablo Picasso, Dolmen Press (Oxford University Press), 1969.

Translations

- (And editor and author of introduction) Andrés Barcia, Chronological History of the Continent of Florida, until the Year 1722, two limited editions, University of Florida Press, 1951, Greenberg, 1972.

- (And editor) Pedro Menéndez, Pedro Menéndez, Captain-General of the Ocean-Sea (autobiography), University of Florida Press, 1953.

- José Suarez Carreño, Final Hours, Knopf, 1954.

- Vicente Marrero Suarez, Picasso and the Bull, Regnery, 1956.

- Rodrigo Royo, Sun and the Snow, Regnery, 1956.

- (And author of introduction) Miguel de Unamuno, Abel Sanchez and Other Stories, Regnery, 1956.

- José Maria Gironella, Where the Soil Was Shallow, Regnery, 1957.

- (And author of introductory essay: “The World of Pío Baroja”) Pío Baroja, Restlessness of Shanti Andia and Other Writings, University of Michigan Press, 1959

- (And editor and author introduction) Jorge Luis Borges, Ficciones, Grove, 1962, published as Fictions, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1962.

- (And editor and author introduction) Camilo José Cela, The Family of Pascual Duarte, Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1964, Weidenfeld & Nicolson 1965, Avon, 1966-71.

- (And editor and author of foreword) Borges, A Personal Anthology, Grove, 1967.

- (And editor and annotator with Sir Herbert Read and, later, others) Unamuno, Selected Works of Miguel de Unamuno, Princeton University Press, Bollingen Foundation, Volume I: Peace in War, 1980, Volume II: The Private World, 1980, Volume III: Our Lord Don Quixote: The Life of Don Quixote and Sancho, with Related Essays, 1967, Volume IV: The Tragic Sense of Life in Men and Nations, 1972, Volume V: The Agony of Christianity and Essay on Faith, 1974, Volume VI: Novel/Niovola, 1975, Volume VII: Ficciones: Four Stories and a Play, 1975.

- (With Alastair Reid) Mother Goose in Spanish, Crowell, 1968. Con Cuba (bilingual Cuban verse) edited by Nathaniel Tarn, Cape Goliard Press [London], 1969.

- (And editor and author of foreword) Borges, Poems, New Writers’ Press [Dublin], 1969.

- (With W. S. Merwin, Reid, and Nathaniel Tarn) Pablo Neruda, Selected Poems (bilingual edition), edited by Tarn, J. Cape, 1970, Delacorte, 1972, Penguin Books, 1975.

- Rafael Alberti, A Year of Picasso Painting: 1969, Abrams, 1972. (And editor and author of introduction) Borges and Adolfo Bioy Casares, compilers, Extraordinary Tales, Herder & Herder, Seabury, 1971, Souvenir Press [London], 1973

- (Adaptor into English and editor and author of foreword and afterword) Borges, Irish Strategies (trilingual edition in Irish, English, and Spanish), Dolmen Press, 1975.

- (With Thomas Rowe) Kamo no Chômei, Notebook of a Ten Square Rush-Mat Sized World: A Fugitive Essay… (adapted from the Japanese Hôjôki), Domen Press, 1979.

- L. M. Vilallonga, The Angel of the Guitar, Ambito Literario [Barcelona], 1979. Reinaldo Arenas, El Central, Bard/Avon, 1984.

- (And annotator) Borges, Atlas, Dutton, 1985.

- (And editor and author of introduction) José Ortega y Gasset, The Revolt of the Masses, foreword by Saul Bellow, University of Notre Dame Press, 1985.

- (And author of foreword) Fernando Arrabal, The Tower Struck by Lightning, Viking, 1988.

Nonfiction

- Gaudí restaurador, o la historia de Cabrit y Bassa, Papeles de Son Armadans [Madrid], 1959.

- Gaudí en la catedral de Mallorca, Mossèn Alcover [Palma de Mallorca], 1960.

- El “Maestro de Santa Úrsula y su mundo”, Papeles de Son Armadans, 1960.

Work as Editor

- Hiro Ishibashi, Yeats and the Noah: Types of Japanese Beauty and Their Reflection in Yeast’s Plays, Dolmen Press, 1966.

Art Criticism

- Title to articles published in Goya magazine, Spain: [4] https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/autor?codigo=2515109 Arts, N.Y.:

- Gaudianism in Catalonia, December 1957.

- Romanesque in Spain, December 1961.

- Pal Kelemen’s El Greco, April 1962.

- Black Knight of Spanish Painting, May-June 1962.

Awards and Recognitions

- Bollingen Foundation grant 1961-1975

- Fellow of the American Council of Learned Societies

- Member of the board of Directors of the American Literary Translators’ Association, 1987

- Member of PEN/Ireland

- First translator to receive a Senior Fellowship in Literature from the National Endowment for the Arts for a lifelong contribution to American Letters, 1988

- National Book Award 1975 for Miguel de Unamuno’s The Agony of Christianity

Personal Achievements

- Private pilot’s license

- Merchant Marine

Other works and Contributions

Regular contributor to Encyclopedia Britannica and Britannica Book of the Year. Contributor of short stories, essays, poems, art criticism and translations to periodicals in the United States, Canada, Ireland, and Spain.

References

- ↑ SKELTON, ROBIN (1969-01-01). Cavalier Poets. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-83764-744-6.

- ↑ Davey, Frank (1972). "The Hierophant". boundary 2. 1 (1): 74. doi:10.2307/302050. ISSN 0190-3659.

- ↑ Kessler, Jascha (1954). "The Tournament". Chicago Review. 8 (4): 23. doi:10.2307/25293073. ISSN 0009-3696.

- ↑ "Anthony Kerrigan". Dialnet (in español). Retrieved 2023-06-11.

External links

This article "Thomas Anthony Kerrigan" is from Wikipedia. The list of its authors can be seen in its historical. Articles taken from Draft Namespace on Wikipedia could be accessed on Wikipedia's Draft Namespace.